This week the first wave of HTC Vive units were delivered to consumers. The Vive is unique amongst the latest generation of Head Mounted Displays [HMDs] in that it also includes a pair of motion-tracked hand controllers. For the first time in gaming, users have the ability to reach out and grab what lies before them – and they fully intend to do so.

Over the course of the last twenty years of 3D gaming there are quite a few awkward conceits to which players have become conditioned. We accept that small obstructions are often unvaultable, that water is generally unswimable, that fragile items are rarely breakable, and that many objects within reach will remain stubbornly immovable. It seems however that when a player is fully immersed in a virtual environment, they are far less willing to compromise on that last point. Like a typical two-year-old, if they can reach it, they will grab it, and when they grab it they are likely to inspect it closely. That presents the artists who create these virtual objects with some unique challenges.

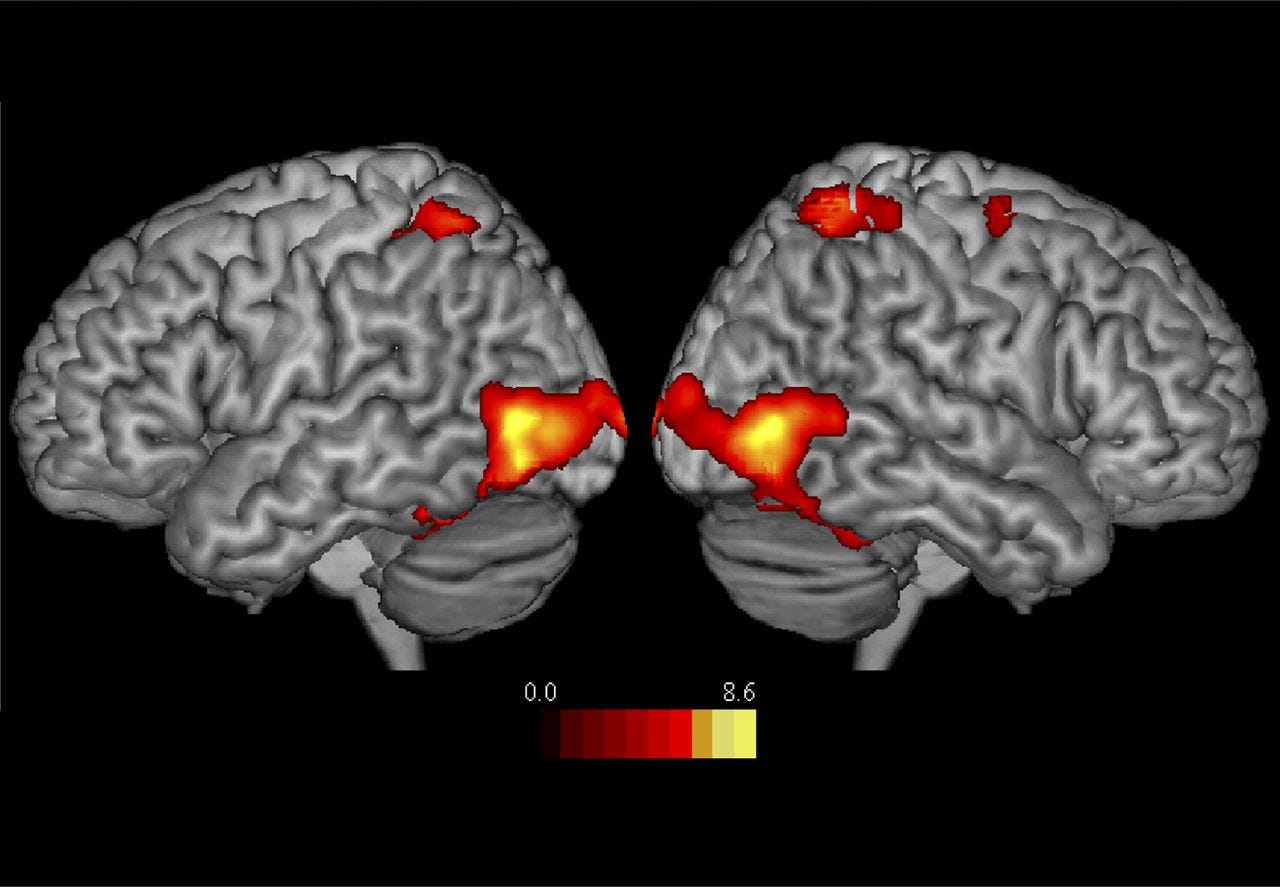

Our brains organize our immediate environment into two different zones based on one’s ability to interact with the objects within them. These can be though of as stuff-within-reach, and stuff-to-which-I-must-walk. As far as the brain is concerned, these are very different areas and different regions of the brain actually light up in an fMRI when one thinks about a given object depending on the zone it occupies. Objects in the near zone, which is bracketed crisply by the proprioceptive bounds of your torso, and vaguely by the reach of your hand is processed by the superior parieto-occipital cortex (SPOC) area of the brain – this is the sweet-spot for dexterity and tool use. Objects beyond that are seen as targets of travel and not really considered by the SPOC, while objects within the near zone trigger our innate desire to examine, manipulate, and assess for utility value.

Our primate brains buy-in to the w0rlds and objects we experience in VR as they do in no other medium. Users’ expectation of object manipulability in these virtual worlds is set not by decades of playing video games, but rather by decades of being humans in the physical world, so objects should be prepared for those interactions as much as possible. These items really shouldn’t ever be welded in place as static props, and should therefore not employ common shortcuts such as unfinished or missing bottom surfaces, or rough textures in areas that “won’t be visible”. They should have geometric and texture detail that can withstand being held within a dozen or so centimeters from one’s face at any angle. Of course these are demanding guidelines when designers are fighting to optimize their experiences to accommodate the high-res 90 frames per second that is required for users to maintain comfortable and plausible presence in their virtual worlds. In the context of VR, it will generally be preferable to reduce the number of objects within reach, than the quality and inspectability of the objects themselves.